‘We Certainly Have a Long Way to Go’

On the one-year milestone of Hurricane Helene, communities reflect on the challenges they still face on the long road to recovery

In 2021, Theo Crouse-Mann and his wife Spring Pearson bought a historic home with a sprawling front porch alongside the French Broad River in Del Rio, Tennessee. They were told it had been raised above the waterline for the 1916 flood, the worst flood on record.

As Hurricane Helene headed their way on Sept. 27, 2024, they were fairly confident that even if floodwaters reached their yard or basement, they and their two young children — then three and five years old — would be all right. But as the river rose to three feet in their living room and they huddled upstairs, they weren’t so sure.

“We were just worried that the house was going to crumble underneath us,” Crouse-Mann shares.

But they were fortunate, he explains. The waters receded enough by midafternoon on the following day that they were able to move to safety.

“It’s kind of still mind-boggling that it’s been a year,” Crouse-Mann says, sharing that after a year of work, the trauma from what they went through is finally starting to settle in.

Soon, they will move back into their home, even though it is still under construction. They had flood insurance, but their payout didn’t fully cover the extent of repairs they needed. Without the support of community organizations, they wouldn’t be where they are today.

“It’s just an ongoing process,” Crouse-Mann says. “A year is like a marker, but it doesn’t really — I don’t even know it means anything in a lot of ways.”

One-year milestone of Hurricane Helene

Hurricane Helene caused an estimated $78.7 billion in damage, according to the NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. In North Carolina alone, the Governor’s Advisory Committee on Western North Carolina Recovery placed the number at $59.62 billion.

In the immediate aftermath of the storm, volunteers and funding poured into the region. National and local media brought attention to the unique horror of widespread flooding in mountainous communities — the devastation of the River Arts District of Asheville, North Carolina, the dramatic rooftop rescue at Unicoi County Hospital in Erwin, Tennessee.

“I saw it, and I still can’t believe it,” says Audrey Jones, executive director of Sunset Gap Community Center in Cosby, Tennessee. “It’s been a year, and still, I’m like, how could this happen?”

Recovery is underway. Many homes have been rebuilt, small businesses have reopened and hard-hit communities are gradually regaining some semblance of normalcy that other areas impacted to a lesser degree were able to achieve earlier in the year.

But to some, “recovery” still feels far from reach.

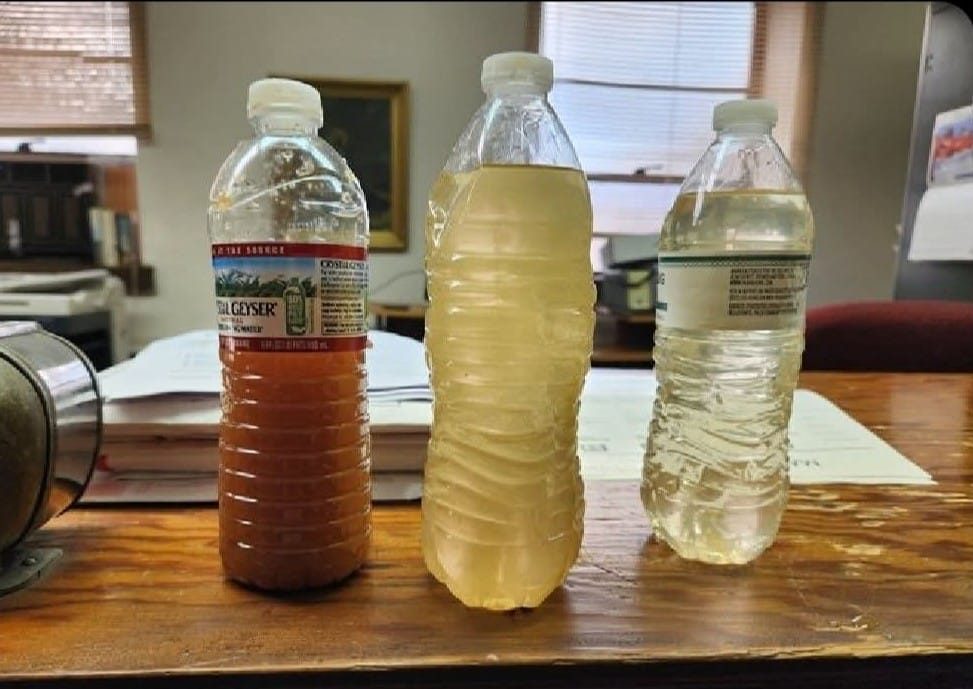

In areas plagued by a lack of affordable housing options, displaced renters live in RVs. Residents whose well water is no longer safe must drink from bottled water. Debris still litters family farms. And some are only now starting to grapple with mental health needs initially left unmet by more pressing physical and economic concerns.

“People just don’t realize we are just getting back on our feet, but with a lot of extra weight and a lot of extra expenses and a lot of changes,” explains Starli McDowell of the Mitchell County Long-Term Resilience Group.

Many communities have launched long-term recovery groups like the one in Mitchell County to support continued recovery. These groups, colloquially referred to as LTRGs, are made up of faith-based, nonprofit, government, business and other organizations, according to the National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster.

“Nothing about disaster recovery is a quick process,” explains Spring Duckett, executive director of the Cocke County Long Term Recovery Group. She estimates that her county is “right around the 20% mark on recovery.”

“We certainly have a long way to go,” she continues.

In Western North Carolina, Sarah Roth, interim executive director of LTRG in Buncombe County, explains that while so much progress has been made in the past year, in some ways, their work has just begun.

“The overall scale of need in Buncombe County is so huge that one year is hardly a dent,” Roth says.

The storm caused significant destruction, but it also exacerbated existing issues. New instances of housing insecurity and mental health concerns bubble to the surface every day — and will for months and years to come. For those doing the arduous work of long-term recovery, it feels never-ending.

“Everybody’s just exhausted,” says Chrissy Miller, a disaster case worker for United Methodist Committee on Relief, and part of the Cocke County Long-Term Recovery Group. “That’s the best way to say it: Everybody’s exhausted.”

Lack of affordable housing, long waiting lists, astronomical repairs

With over 7,600 displaced households in North Carolina alone, housing continues to be one of the primary challenges plaguing impacted communities.

“We already had an affordable housing crisis before the storm, and it’s really only gotten worse,” says Sarah Roth about Buncombe County, North Carolina, which is home to the city of Asheville. From her perspective, the loss of available units combined with rising costs have exacerbated an already difficult situation.

“We’re going to start to see more people move away from our community, because it becomes impossible to live here,” Roth adds.

Many displaced residents are living in donated campers without clear paths forward. Some homeowners, McDowell explains, are just now coming to terms with the fact that they might not be able to move back home, even after months of combating mold and water damage.

Displaced renters without affordable housing options are Duckett’s biggest concern.

“When you’re economically distressed, you just don’t have the funds, the capital, to be able to come up with all of the deposits and the new levels of what’s expected for rent,” Duckett explains.

This massive need for housing solutions and home repairs is putting a strain on existing resources, such as PODER Emma, an organization supporting the Emma community in Buncombe County, North Carolina. Kelvin Bonilla, home repair program manager for PODER Emma, shares that they just don’t have the staff or contractor capacity to meet all the home repair needs that are brought to them.

“We have a waiting list that is far too long,” Bonilla says. “[It’s] to the point that some folks are having to resort to putting themselves into really high debt just to be able to fix a roof,just because we haven’t been able to get to them yet.”

And sometimes, that price tag is just too “ridiculous” or high to fathom, explains Sophia Phillips, director of the Appalachian Rebuild Project, who also serves as the communications chair and volunteer coordinator for the Mitchell County Long Term Resilience Group in North Carolina.

“The biggest things that are left behind are because they’re so big that nobody can tackle it, like a $100,000 bridge to a single person’s residence,” Phillips says. “It does sound ridiculous to spend $100,000 to access a single person’s residence, but what else is an individual to do except literally walk across the Cane River to get to their home?”

The struggle to revitalize local economies

![“We didn't have flood insurance, because who could afford that, and nobody ever saw this coming,” shares Michelle Cuellar, owner of Bean Tree Cafe, a coffee shop and the post office in Hartford, Tennessee. She had experienced high-water events before, even having water come up to her restaurant’s deck, but never to this level. “[After] 22 years of being in business, we had everything we needed, all the industrial equipment,” she says. “All my needs were met. I had all the things that it takes to run a very busy industrial restaurant, and in one fell swoop, I lost it all. I lost my livelihood.” In August, Cuellar reopened the Bean Tree Cafe for a few days a week at a much smaller scale than she operated previously. Photo by Abby Hassler](https://appvoices.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/DSC8357-1024x683.jpg)

Loss of jobs, small businesses and industry is a reality felt across much of the region impacted by Helene. Many long-term recovery workers expressed a desire for more resources for small businesses.

This July, Mountain BizWorks, a nonprofit financial institution based in Western North Carolina, released a 2025 Local Business Impact Survey of 700 small businesses. The report found that 93% of respondents have reopened after the storm, but 86% said that earnings were at or below pre-Helene levels — half were down 20% or more.

Some businesses in rural areas, like Michelle Cuellar’s Bean Trees Cafe in Hartford, Tennessee, struggled to access resources for months and are just now reopening, but at a smaller scale.

“I am tough, but this almost broke me,” Cuellar says.

The tourism-dependent area of Damascus, Virginia, was hit hard by the loss of the upper 18-mile portion of the popular Virginia Creeper Trail. Visitors can still ride the lower stretch of the trail, or the “Start to the Heart” from Abingdon to Damascus, which reopened quickly after the storm.

Though the tentative reconstruction timeline for the upper section has been announced for fall 2026, the city shared that “based on anecdotal reports from Damascus bike outfitters, bike rental and shuttle traffic on the [open section of the] Virginia Creeper Trail is down an estimated 70% to date for the 2025 season.”

In Unicoi County, Tennessee, Suzy Cloyd, executive director of the county’s LTRG, shared that the loss of industry jobs is her biggest concern after having “the entire industrial park pretty much wiped out.”

“Workforce development is probably the biggest challenge for Unicoi County, just because industry in itself is not back to 100%,” Cloyd says.

Exposure of existing food insecurities

In June of this year, the MANNA FoodBank in Asheville, North Carolina, reported 190,000 visits to its pantries — its largest month on record.

“Our numbers are consistently staying at the highest, most sustained rate of people visiting our pantries every single month in our 42 years of history,” says Micah Chrisman, director of marketing and communications at MANNA FoodBank.

One of MANNA’s food pantry partners is Mitchell County Shepherd’s Staff in Spruce Pine, North Carolina.

“Before Helene, we were serving something like 400 households a month,” says Starli McDowell of the Mitchell County Long-Term Resilience Group, who also serves as the director of the Mitchell County Shepherd’s Staff. “Now we’re serving 1,700 households, and the need is growing.”

Multiple factors other than the storm contribute to increased need, explains Chrisman, including the high cost of living, wage stagnation and food access in rural areas. However, it tells a story about how people are struggling to rebuild parts of their lives.

“Rich or poor, these folks are coming to these community partners and MANNA to get food, because it just might be the only place within a 45-minute drive or longer to get fresh food in their local area,” Chrisman says.

Mitchell County lost one of its two major grocery stores to Helene.

“They come to us and then go to Walmart to supplement what we don’t have, because Walmart’s the only store we have,” McDowell says. “Our Ingles flooded out. So it’s us and Walmart.”

Looking ahead: Funding uncertainty and adjusting to a ‘new normal’

“The long-term recovery part of disaster relief is the most underfunded — historically underfunded — portion of disaster response,” shares Lisa Ford, vice president of strategic engagement and communications at the East Tennessee Foundation.

Out of the $59.62 billion in total estimated damage in North Carolina, the state has directed $3.1 billion in state funds to Helene recovery. The state has received $1.8 billion in federal funds, and the federal government has allocated an additional $3.4 billion that has not yet been disbursed. Almost $7 billion in insurance and private funding has come in or is in the process of being distributed in the state.

These funds are a small drop in the bucket of the remaining $44.71 billion in need, according to North Carolina Gov. Josh Stein’s recent federal funding request on Sept. 15, 2025. The current share of federal aid for Helene also sits at 9% of total damages, a figure far lower than previous federal responses to major hurricane recovery efforts, including Hurricane Irma at 32% of $64 billion, Hurricane Maria at 73% of $115 billion, or Hurricane Sandy at 78% of $88 billion.

The governor has requested an additional $13.5 billion from Congress.

“Just like folks in the Gulf states, the mid-Atlantic, and Puerto Rico, the people of western North Carolina deserve federal support after a major hurricane, and the time to act is now,” stated Governor Josh Stein in a press release about the announcement.

In Tennessee, the state awarded $41,353,959 to 126 projects through its Governor’s Response and Recovery Fund in July 2025 — far less than the $261 million received in funding requests. One awardee is the Cocke County Long Term Recovery Group.

“The resources that we have amassed and been working with over the last year have been amazing, but we certainly do not have anywhere near what we need to make it to the finish line,” says Duckett of the LTRG. The group receives additional support from the East Tennessee Foundation and other sources.

“The work isn’t done,” Duckett continues. “We still need skilled volunteers, we still need resources, we need funding.”

In the meantime, many are having to adjust to a “new normal.”

“There was a ton of damage to our environment, and yet spring and summer make things green,” Sarah Roth of Buncombe County says. “It sort of covers up a lot of the scars of our mountain region, but they’re still there.”

“[That] aligns with the human aspect of it,” Roth continues. “There might be cleanup that has happened, and it looks better, [but] there’s still scars that people are trying to heal and recover and rebuild.”

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment