Virginia Gold Rush

By Dan Radmacher

It should have been a time for the Buckingham County, Virginia, environmental community to celebrate and recuperate from a bruising but successful battle to stop the Atlantic Coast Pipeline and a compressor station planned for Union Hill.

“We were elated and exhausted with word of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline cancellation,” says Chad Oba, president of Friends of Buckingham, a group that spearheaded local opposition to the pipeline.

But any hopes that the group and others in the area could stand down after Duke Energy and Dominion Energy announced they were canceling the controversial project in July 2020 — largely because of increased costs from a series of lawsuits forcing the pipeline to adhere to environmental regulations — were dashed when disturbing news of a potential gold mine in the county came to light.

When he first heard there might be gold near his property from two Canadian geologists who showed up at his door asking if they could take samples from a creek on his property, Paul Barlow was actually a bit intrigued.

“At first, it was, ‘Like, wow, wouldn’t it be cool if we had a vein of gold under our property?’” says Barlow, a retired electronics technician who moved to Buckingham County in 2012.

But the more he thought about it — and the more he learned about the kind of open-pit mining that would be used to extract the gold — the more concerned he became.

“I asked the geologists how they would get to the gold, if they would sink a shaft,” he says. “I didn’t know anything about gold mining. They said, ‘You don’t understand. We’d buy your property, level your house. All these hills and trees you see would be gone.’”

That’s when Barlow realized that having gold under his property — or anywhere near his property — could ruin his life. “We like the peace and quiet out here,” he says. “It’s worth millions of dollars.”

That peace and quiet could be shattered if Aston Bay, the Canadian prospecting and mineral exploration company that’s been doing exploratory drilling around Buckingham for several years, moves forward with a mine near his property. Aston Bay has leased mineral rights on around 11,000 acres of Central Virginia forestland owned by Weyerhaeuser, a real estate company that harvests timber.

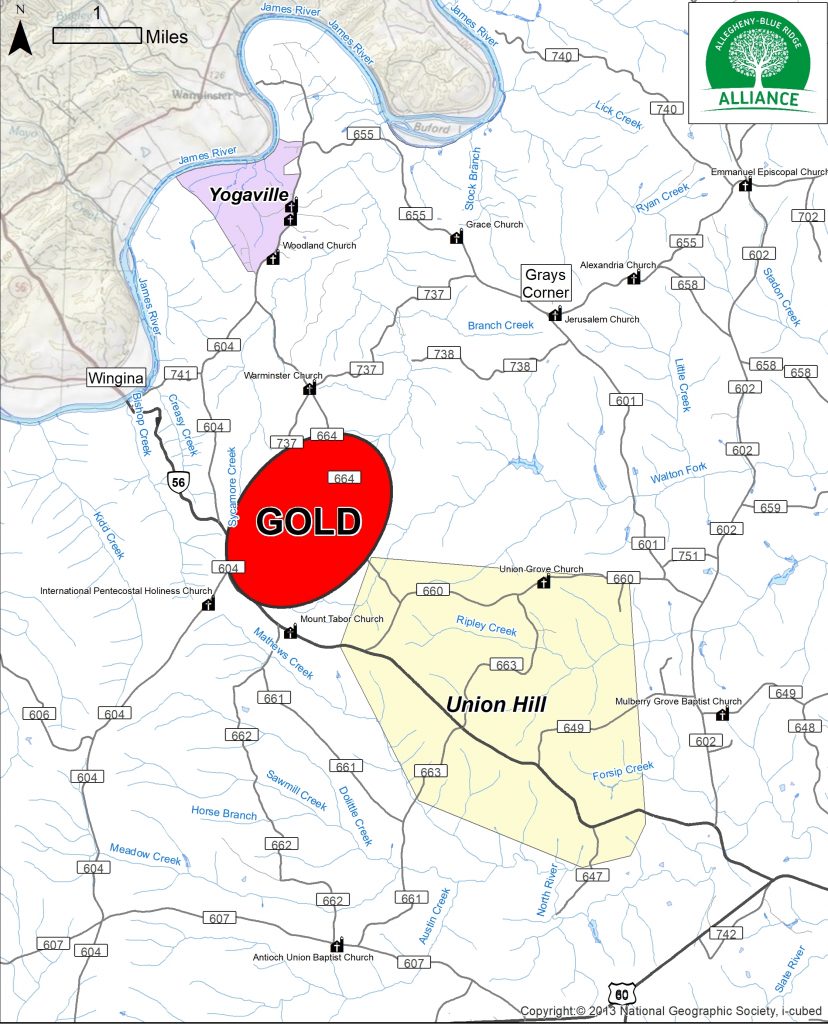

Map shows Aston Bay’s area of gold exploration interest in between the Union Hill and Yogaville communities. Map created by Dan Shaffer of Allegheny-Blue Ridge Alliance.

“We know that Aston Bay just sold some of their rights in Canada — mineral or leasing rights,” says Stephanie Rinaldi, Barlow’s neighbor who is working with Friends of Buckingham to oppose the possible mine. “Now they have some cash, and we’re concerned they’re going to start doing even more exploration.”

Friends of Buckingham wasn’t looking for a new fight. “It was bad news, quite simply,” says Oba. “We weren’t prepared to jump right back in to mount a campaign against this. Thankfully, there were people like Stephanie able to provide additional help.”

It was a different kind of fight than the battle against ACP, according to Oba. “The process is different,” she says. “This involves permitting from the Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy. It’s a different ballgame. But we still have the same allies. And we could bring all the things we learned as an organization to the table. It made sense for us to take the lead.”

“It was disheartening to see a community that had just gone through such a fight would have to face another toxic foe,” says Jessica Sims, Virginia field coordinator for Appalachian Voices, the nonprofit organization that produces The Appalachian Voice. “But Friends of Buckingham are an incredible group of neighbors looking out for each other and for each others’ futures.”

Modern Gold Mining Involves Enormous, Deep Pits

First, people had to educate themselves about modern gold mining. Barlow did some research and found that gold had been mined in and around Buckingham for about 30 years back in the 19th century, ending in 1849 when the gold rush in California drew off all the miners.

Mining then was accomplished with picks and shovels. Old gold pits, mostly overgrown, still dot the landscape.

Modern gold mining is completely different, Barlow found when he drove down to Kershaw, South Carolina, where one of the largest gold mines on the East Coast has been operating for about four years. As he drove near the mine, the scale of modern operations became evident when he began seeing dirt mounds piled seven or eight stories high.

“These pits are huge and they displace so much earth they just have to pile it up somewhere,” Barlow says. “The operation is already 5,000 acres, and they just keep expanding.”

Stephanie Rinaldi keeps bees and was considering starting a small business in Buckingham County. But the prospect of a massive gold mine nearby could change those plans. Image by Friends of Buckingham

The Haile Mine, operating about three miles from Kershaw, has multiple pits, each hundreds of feet deep. Gold ore — predominantly quartz and other minerals containing minute fractions of gold as low as 0.03 ounces per ton — is processed by pulverizing it and then spraying huge piles of ore with a cyanide solution that leaches out the gold (and some silver), which is then recovered from the solution.

During the processing, mercury contained in the ore can be released into the air. The operators of the Haile Mine were recently fined more than $100,000 for excessive mercury emissions. After gold and silver are extracted, the leftover toxic sludge is pumped into tailings ponds — one of the many threats gold mining poses to drinking water in the region.

“Drinking water is the main concern,” says Rinaldi. “Cyanide-soaked ore leaks into the ground water. Acid mine drainage from exposed sulfide in the pit will be a forever problem as long as the stuff is exposed. Ground water fills up the pit, which has to be pumped out, drawing down the water table.”

According to Oba, residents have reported issues with wells just because of the exploratory drilling, including Warminster Baptist Church, which had to replace its well.

But the threats of toxic leaching or catastrophic failure of the earthen dams typically used for these operations are especially concerning given the proximity of the area to the James River. According to an interactive map put together by the Allegheny-Blue Ridge Alliance Conservation Hub, the river is about two miles from the center of the exploratory drilling that has taken place.

“If you let these people come in and put in these waste lagoons, it’s not a matter of if but when this happens, and then it all goes in the James,” says Barlow. “The James River is the source of drinking water for over 3 million people. It flows into the Chesapeake Bay. Decisions made in Buckingham County are dictating the future for half of Virginia. This could be devastating to the fishing industry and millions of people.”

“It Wasn’t El Dorado, I Can Tell You That”

Local officials seemed more interested in the potential windfall of a gold mine than the environmental and public health threats, according to Barlow. David Brown, owner of Buckingham Land and Timber and one of Aston Bay’s local partners, promised the Buckingham County Planning Commission during a July 2020 meeting that if a gold mine goes forward, “it’s a big payday for the county, it’s a big payday for us, it’s a big payday for everybody concerned.”

According to The Farmville Herald, Planning Commissioner Patrick Bowe asked at a later meeting, “Why would we consider not thanking them for looking for gold?”

In South Carolina, the director of operations at OceanaGold-Haile Gold Mine states that the company has an $87 million annual economic impact in the county where the mine is located. But when Barlow visited Kershaw, he didn’t see evidence that the nearby gold mine brought much value to the town. “It wasn’t El Dorado, I can tell you that,” Barlow says. “There are potholes in the streets and probably 30 percent of the storefronts are boarded up.”

Paul Barlow describes his visit to Kershaw, South Carolina, during a video produced by Friends of Buckingham for a webinar about the potential gold mine. Image by Friends of Buckingham

Buckingham leaders don’t seem to understand the consequences, according to Rinaldi. “It’s been really frustrating trying to explain to the people in charge,” she says. “It is so hard to get them to understand how serious this is. Everyone is just brushing it off. Buckingham does need the jobs, but we know those jobs wouldn’t last. Mining is a boom and bust economy.”

The county refused to take action against the company for the exploratory drilling that opponents said was illegal without a special use permit. But then the county Board of Supervisors voted in January 2021 to allow exploratory drilling by right on land zoned for agricultural uses, meaning no special permit is required, though drillers still need permission from landowners.

“We knew right away we weren’t going to get much support from the county,” says Oba. “The legislature was about to meet, so we decided to try to get a bill passed, hopefully with a moratorium on gold mining in the state. Open-pit modern gold mining has never been done here in Virginia.”

The group found some sympathetic ears in the General Assembly. “The prospect of an open-pit gold mine a few miles from the James River should give us all pause,” said Del. Elizabeth Guzmán during an educational webinar co-hosted by the Friends of Buckingham and the Virginia League of Conservation Voters.

Guzmán sponsored a bill in the Virginia General Assembly to put a moratorium on gold mining in the state while a commission studies the impacts. The final version of the bill didn’t include a moratorium, but does call for a study to be completed by Dec. 1, 2022. “This was the best that was going to get out of the Senate at that time,” Guzmán says.

“We got a bill passed,” Oba says. “It was very watered down. We did our best. It’s a learning process.”

A Community in the Crosshairs, Again

While the study commission comes together, local residents remain uncertain of the future. Deacon Willie Perkins, Jr., of the Warminster Baptist Church also spoke during the educational webinar.

“It’s like we’re starting all over again,” he says. “In the beginning, it was the pipeline. Now it’s gold. It’s one more thing to affect the African-American neighborhoods. Our community is really outraged with this Canadian company that’s coming in that doesn’t care who they affect. I’m deeply concerned about our church, our cemetery. Once they start doing an open-pit mine, they’re not going to dig around our cemetery or our church. I’m thinking they’ll just roll over it like it’s not even there.”

Deacon Willie Perkins, Jr., behind the sign, stands with four members of Warminster Baptist Church. Members say they have already seen well water changes in the neighborhood as a result of exploratory drilling. Image by Friends of Buckingham

Oba doesn’t think it’s a coincidence that, once more, an African-American community is in the crosshairs. “I see this as another instance of systemic racism,” she says. “They thought this looked like a good area. Who’s going to question this? I am extremely concerned about this.”

His trip to Kershaw left Barlow shaken. The mine is very disruptive to the surrounding community, according to Barlow.

“It’s in operation 24 hours a day, with hundred-ton dump trucks hauling ore,” he says. “When I was talking to residents living near the mine, I could hear the constant back-up beepers and diesel equipment going all the time. There was just a lot of noise, dust and smoke.”

Driving around county roads near the mine site, Barlow saw a lot of “ghost driveways” where the mining company had bought up houses and razed them.

“Now there are just mailboxes, fences and overgrown lots,” he says. “It’s very dystopian.”

Family homesteads and farms that had been there for hundreds of years are now just gone, swallowed by the mine, according to Barlow.

“I’ve seen Kershaw, and I’ve seen the future of Buckingham,” he says. “It’ll be devastated.”

Interactive map by Allegheny-Blue Ridge Alliance

Related Articles

Latest News

More Stories

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment