Mountain Wind

Wind power has had a very successful decade. Between 2006 and 2016, global capacity has grown over six-fold to 486.7 gigawatts, according to the Global Wind Energy Council. Though the United States has lagged behind China and the European Union, capacity grew from 11 gigawatts to 82 gigawatts from 2006 to 2016.

If construction moves forward on the Rocky Forge Wind project, simulated here, it would be Virginia’s first wind farm. Image produced by Apex Clean Energy

Only one region of the United States lacks any significant installed capacity, according to a recent report by the U.S. Department of Energy: the Southeast. According to the DOE, only 0.2 percent of the energy produced in the Southeast is generated by wind power. This is not unexpected, the wind just does not blow that hard in the Southeast. Average wind speeds at turbine-height are far lower than the rest of the nation.

In Appalachia, significant wind energy is being produced only in northeast West Virginia and southwest Pennsylvania.

But if plans by Apex Clean Energy come to fruition as expected, wind turbines will soon begin spinning in the Appalachian Mountains of Virginia. The Rocky Forge Wind project in Botetourt County has received all of the necessary permits, though it currently does not have an anticipated start date, according to Apex Development Manager Charlie Johnson. The project is planned to generate up to 75 megawatts of electricity from 25 turbines.

Jerry Fraley, who owns the land the project will be built on, was looking for an enduring way to pay for the upkeep of his family’s 10,000-acre hunting and wildlife preserve so his grandchildren and great-grandchildren could continue to enjoy it. A deal with Nestlé to tap North Mountain springs for Deer Park Spring Water had just fallen through when the big power line that cuts across the property caught his eye. He started thinking about the potential for wind power at the top of North Mountain.

“I got to thinking about what else I could do and called AEP [Appalachian Electric Power],” Fraley says. “I knew if you had a power line and substation, you’re way ahead for wind. The power line turned out to belong to Dominion.”

Discussions with Dominion eventually led him to Apex Clean Energy, a relatively new energy company that has been completing wind power projects at a brisk clip.

“Apex is an outstanding group of people,” Fraley says. “They really have the public in mind.”

According to Johnson, Fraley’s property is ideal for the project.

“The rural piece of private property where Rocky Forge is sited has a strong wind resource, on-site transmission and compatible land use, which makes it one of the best sites in the commonwealth for a project,” he says. “The project also received many endorsements, as well as significant public support from the county, region and state as a whole.”

The 78-year-old Fraley has a deep connection to the land. His ancestors on his mother’s side lived in Botetourt County as far back as the mid-1700s.

“It’s important to realize where you come from,” Fraley says. “I feel an obligation to the land of my ancestors.”

A former coal mine operator, Fraley is a renewable energy proponent.

“Our country is a great country, made strong on its natural resources,” he says. “We need to use them wisely. The supply of coal is being depleted. The long-term future of energy is in renewables.”

The project attracted the strong support of the Roanoke Group of the Virginia Chapter of the Sierra Club, according to John Williamson, member of the Botetourt Board of Supervisors. “The Sierra Club showed up at every meeting,” he says.

Other environmental groups — the Roanoke Valley Cool Cities Coalition, the Chesapeake Climate Action Network, the Virginia Student Environmental Coalition and the Virginia Conservation Legacy Fund — support the project.

According to Dan Crawford, chairman of the Sierra Club Roanoke Group, there was far less opposition to the Rocky Forge project than for a proposal to put turbines on Poor Mountain. That project has been tabled until the fate of the Mountain Valley Pipeline is resolved.

Getting Sierra Club support for both projects took a bit of doing, he says. “I had to get a little aggressive,” he says with a smile. “The chairman at that time was a little timid and argued for a neutral position. That’s not the Sierra Club, though. We don’t do the middle ground. It’s either right or it’s not.”

For Crawford, the calculus is simple with the threat of climate change looming.

“By a wide margin, wind is your most productive clean energy source, dollar to kilowatt,” he says. “That’s shifting as solar drops in price, but it is still the best way to get energy for the buck. We may see the day when solar is the bigger answer, but we know that right now we need as much wind or solar energy as we can build yesterday. We don’t have time to tiptoe around.”

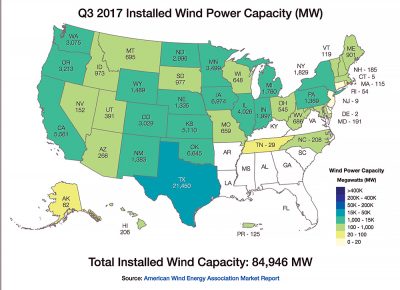

Click to enlarge. Source: American Wind Energy Association Market Report. Map by U.S. Department of Energy WINDExchange

Opponents to the project, who formed a group called Virginians for Responsible Energy, worry about the blasting and grading that will need to be done on the mountain’s steep slopes, as well as the loss of hardwood forest that will have to be cleared for access roads. Their website notes, “The turbines will be brightly lit and will be visible throughout the Shenandoah Valley.”

Bird mortality is also a concern of opponents. The website discusses an incident at the Laurel Mountain wind facility in West Virginia when nearly 500 birds were killed when they collided with structures near the turbines on one foggy night in 2011.

Crawford doesn’t dismiss concerns about bird mortality, but thinks they need to be put in perspective.

“The Audubon Society has studied the issue for a long time,” he says. “They worked closely with Stanford University and the Smithsonian and determined that for every bird killed by a turbine, 10,000 birds die from something else we do — from tall buildings to cell towers to unmanaged pets. As long as turbines are properly sited, the price that we pay in wildlife loss will be worth the gains in clean energy.”

As for viewshed concerns, while Crawford can understand why people might not want wind turbines right in their backyards, he does not see them as marring the landscape. “They’re beautiful compared to all the other [junk] we live with,” he says.

With the Rocky Forge project, Botetourt County saw an opportunity not just for up to a million dollars a year in additional tax revenue at its peak, but to develop a wind project siting ordinance that worked, according to Williamson.

“My thinking was that $1 million a year is great, and we hope it’s built,” he says. “But we also saw that the county had an opportunity to do the ordinance right and do the project right and, in addition to adding to the local tax base and creating local jobs, actually make a contribution to renewable energy in the commonwealth. If we could do this right, maybe it can be a model.”

In developing its ordinance, the county mostly concentrated on erosion concerns, Williamson says, and the water quality impairments that could result, especially during construction. “Concerns about migratory birds and bats, I frankly considered the state’s purview,” he says. “We discussed it and evaluated it at the local level to some degree, but we largely deferred to the state.”

The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, following a process laid out in a 2010 state law, approved measures proposed by Apex to protect bats by turning off turbines at night during the summer months when bats are most likely to be flying. They also accepted Apex’s assurances that large numbers of the types of birds threatened by turbines aren’t present at the site.

Apex called the county permit process “one of the most comprehensive we have seen to date.”

“We worked with Botetourt County officials to help them understand the project and answer questions throughout the permit process, leading to a unanimous permit approval,” Apex’s Johnson says. “As the first potential wind farm for Virginia, we want to develop Rocky Forge responsibly and set the bar high for future projects.”

Crawford hopes this will be far from the last wind project approved in the region. “We could use at least six or eight wind farms along the spine of the Appalachians,” he says.

Offshore wind projects are also promising, according to Crawford, though the expense of constructing turbines in the ocean makes them far more costly.

“Generally, offshore costs twice as much,” he says. “Having worked on the water, I know why. Just look at the cost of hiring a truck driver versus the cost of hiring a skipper.”

Still, offshore projects are being built. The nation’s first offshore wind project came online in 2016, the 30-megawatt Block Island Wind Farm off the coast of Rhode Island. Projects off of Kitty Hawk, N.C., and Virginia Beach are also in the works. There’s much more wind potential offshore in the Atlantic than inland in the Southeast.

“Offshore is coming,” Crawford says. “I’m excited. We need wind and solar anywhere we can put it. Even if we pay twice as much for offshore, it’s still less than what we’ll pay if we don’t do it.”

Editor’s Note: This article was updated on Dec. 5 to reflect more recent global wind energy statistics. The print edition stated the global wind energy capacity is 432 gigawatts, which is the 2015 number. The 2016 report from the Global Wind Energy Council puts the number at 486.7 gigawatts.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

5 responses to “Mountain Wind”

-

For what its worth,compare the price of wind produced energy to the damage done by mountain topping. i.e. the poisoned streams detroying the wildlife, the damaged landscape crippling the habitats, not to mention the human suffering plus to attempt to fix this mess.

I wonder why there are those who complain about the bird killing, killings which I do not minimize nor ignore, are the same people who support a leader whose glass buildings kill more birds than all the wind turbines combined. These same people also ignore aforemented costs of clean and health while claiming subsidies for wind farms are excessive. A properly considered survey would find that had the wind turbines been installed say 45 years ago they would be providing revenue for their respective states instead of these states requesting aid for the damage. -

What is not said in this article is grid operators rate wind energy to be about 13% of the installed power. In other words, they only expect about 13% of the 83 gigawatts quoted above. More importantly, this power is intermittent. The grid operators do not know when the power will be available. I live about 2 miles from the proposed RF project. We had almost no wind from mid-July though September, a time when the US is experiencing peak energy demand.

Also not discussed in this article is what these massive wind turbines are doing to rural life. The noise, both audible and inaudible are causing real harm. All one needs to do is search what is happening in Maine, Vermont, and New York to find multiple articles about health effects on farmers and their families in close proximity to these massive structures.

Finally, one thing the article gets correct is that there are very few wind turbines in the southeast because the wind does not support their construction. Visit the Department of energy website and view their wind maps.

-

One of the challenges is to educate the public, the taxpayer where the wind speed will support wind farms. This is key.

-

DOE states that there is only 8 GW (equal to 8 large power plants) of wind potential in the Southeast at the current tower limit of 80 meters height. There is over 200 times this potential above 140 meters. Land based wind in the Southeast could supply over 3 times the electricity now consumed and provide thousands of dispersed jobs. DOE has stated that my technology to access this wind resource has merit but they do not have the resources to support peer review.

-

An admirably clear and complete article. Thanks.

Leave a Comment