Service, Music and Community at Appalachian South Folklife Center

Influential center in southern West Virginia celebrates 50 years

The chapel is used for spiritual gatherings, weddings, meetings and concerts. Photos courtesy Appalachian South Folklife Center

By Peter Slavin

The Appalachian South Folklife Center in southern West Virginia has weathered many storms over the past half century, yet continues to provide help to residents in need, education for youth, and a safe harbor for activists. Despite early denunciations of its founder’s political views, government harassment and a fire, the center has become a gathering point for locals and visitors drawn to the center’s beautiful setting, music and opportunities for service.

Since 1965, the center’s staff and volunteers have worked to improve the lives of Appalachia’s people and to instill in them pride in their heritage, while also giving others an appreciation of the region. The center has focused on educating young people and dispatching volunteers to assist local residents who need home repairs. The center has also opened its doors to people needing a place to meet, from Miners for Democracy and opponents of a high-voltage power line to campaigners against mountaintop removal coal mining.

The center is also known for its music festivals, ranging from the early Mountain Music Festivals that drew thousands to hear both traditional and contemporary folk songs to the more recent CultureFest, an annual event featuring world music. Pete Seeger, Merle Travis and Hazel Dickens as well as local singer-songwriters and garage bands have played on its stage. “Hardly any event doesn’t include music,” says Mary “Meno” Griffith, who first came to the center in 1969. “Even after long meetings about serious issues, someone gets out an instrument and starts singing.” Music, Griffith says, is central to the center’s mission, because it brings people together and “helps us understand our history.”

Still, if music has been the soundtrack of the center’s life, making Appalachians aware of their history and culture and its value has been its central purpose.

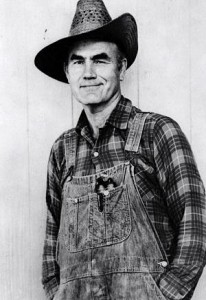

The Folklife Center was the creation of Don West, a north Georgia farmer and champion of displaced mountain people, tenant farmers and union workers, and his wife Connie, a portrait painter. A man of many talents, Don was a leading poet in his day, and a respected educator, political activist, labor organizer and minister.

Don West was raised on a North Georgia mountain farm in an area that had flown the Union flag during the Civil War and nonconformity was part of his heritage.

According to “The Cry Was Unity: Communists and African Americans, 1917-1936,” West was “wanted dead or alive” for defending a black man who was on trial for leading a hunger march, and fled Atlanta under a pile of sacks in a car. Because of his civil rights activism, the Ku Klux Klan once burned down his home. In 1932, he cofounded the historic Highlander Folk School in Tennessee — now the Highlander Research and Education Center — a critical training ground for the labor and civil rights movements. Almost forgotten today, Don West attained near-legendary status in the South in the era before the civil rights movement.

The Wests saved enough while teaching for a decade in Baltimore to purchase a 600-acre farm in the beautiful hills north of Princeton, W.Va., so they could build a new folklife center in 1965. Over the years, the United Church of Christ, Quakers and other progressive churches have been the center’s primary financial supporters; many individuals have also donated.

In the beginning, Don West used produce from a big garden on the farm to help feed those at the center, and raised and sold hay. The farm is no more, having been divided among his children at his death in 1992. The center now occupies 63 acres.

In the early years, people in the community who were facing tough times, including striking coal miners, knew they could go to the center for help. “If they needed a meal, there was always food there and always something to do to earn it,” says BobMac MacMillam, who has worked at the center on and off since 1973.

Between 400 and 500 people come to do service work each year for up to 40 families. Photos courtesy Appalachian South Folklife Center

Griffith tells one story about Don West’s influence on someone who became a noted writer. “Jeff Biggers was hitchhiking … just young and figuring what he’s doing in world. Don West picks him up, takes him to the Folklife Center, feeds him, charms him with stories, and becomes a mentor to him. And you hear that story over and over again [from] people who are associated with the Folklife Center.”

From 1968 to 2000, the center sponsored a residential summer camp, bringing in as many as 50 disadvantaged 11- to 16-year-old boys and girls from all over Appalachia. The aim was for the kids to enlarge their horizons, learn about the region’s history and heritage, counter stereotypes they faced, and boost their self-esteem. The kids learned about coal mining, black lung, organizing and unions as well as outside domination of the region and its impact in holding Appalachia back. Many campers came back year after year.

Because of Don West’s politics, some people in the community felt animosity toward the center. For years, the Wests took part in political demonstrations and marches, and sometimes they brought along summer campers, says former executive director David Stanley.

So when the dining and meeting hall, long the heart of the center, burned to the ground in the early 1970s, some believed the fire might have been set. But the cause was never determined, and the hall was soon rebuilt.

Several women in the back-to-the-land movement founded the Learning Day Camp in 1985. The camp continues today and reportedly has a powerful impact on children. Photos by Brandi Massey

Stanley says in the late 1980s two men came to his office and demanded to know where the center got its financing. They said they were from the state, but displayed no badges. He refused to produce his records and told them to leave. A year or two later, he says, Internal Revenue Service agents “took Don West out of his house … at 2-3 in the morning, took him down to Princeton to interrogate him about his finances.”

Stanley calls the incidents government harassment.

Every year 400 to 500 out-of-state high school students come for a week to participate in service work, assisting local communities while learning about Appalachia’s culture and history. In groups of 15 to 20, the students work on home repairs for low-income, elderly and disabled people — painting, building a new porch or deck, replacing rotting bathroom floors and the like.

“You have to prepare yourself for it,” says Briddy Blankenship, a previous executive director. “It’s very humbling to see how some people are living.”

Upcoming Events at the Folklife Center

- Earth Day, April 23, 11 a.m. – 11 p.m. — Music, arts, and activism, including an herb walk, panel on local foods, sustainable building demonstration, yoga, drum circles, live music, open mic and jam session. Free. Call: (304) 466-0626 Visit: earthdaywv.com

- Want to bring a group on a service trip? Email Laura Lavernia at appalachianfolklifecenter@gmail.com

Culturefest, Sept. 8-11 — World music & arts festival with four stages for music and dance, unusual workshops, children’s activities, roaming dancers acting out stories, and on-site camping. $10/day; $50/weekend. Call: (304) 320-8833 Visit: culturefestwv.com

The groups only work for five days and don’t do electrical work or plumbing, says Blankenship, “but we can still do a lot to make a difference in someone’s life.”

Not only the homeowners benefit, notes Griffith. The young volunteers — mostly middle class suburban kids — have their eyes opened to how some people have to live, she says, and learn they can “give back for the blessings in their lives.” The kids also make their own meals and sleep in dormitories. In the evening they learn about Appalachian life, from mining history to pottery and square dancing. Some groups have been coming back for 15 years.

The center also offers a unique day camp program for one week each summer for at-risk children ages four to 12. Families pay what they can afford. The campers and their counselors — junior high, high school and college students, virtually all of whom attended the camp as children — go together to classes such as science, math, journaling and yoga taught by certified teachers. The counselors provide powerful role models, says assistant director Sarah Justice.

“Everything we do is hands-on,” Justice says. “Kids leave each day with things they’ve made in arts and crafts.”

“Many kids live way down a dirt road with the closest neighbor maybe being two miles away,” she notes. For them, she says, the chance to socialize with kids their age is special.

Citing the slurs against Appalachians on TV and other media, Justice says the kids’ camp combats the “cultural shame associated with being from Appalachia.” The camp celebrates their West Virginia heritage.

For Griffith, being part of a community of like-minded progressives at the center who put their values into practice through programs like the kids’ camp means a great deal. She has served on the board for 28 years. “It’s like the Folklife Center is my church,” she observes.

But it wasn’t through a program that the center touched local resident Doris Irwin’s life. She first went there to listen to music as a 20-year-old high school dropout who had felt the sting of Appalachian stereotypes growing up. After she started spending time at the center, she came to see her culture and herself differently. Irwin learned “you don’t have to be limited by your past,” and saw that education “was not something out of my reach.”

Several women in the back-to-the-land movement founded the Learning Day Camp in 1985. The camp continues today and reportedly has a powerful impact on children. Photos by Brandi Massey

She wound up going to college, earning two degrees and having a long career as a registered nurse and social worker.

Over the decades, the center has changed, too. In recent years local people have started holding their weddings, celebrations of life, family reunions, church services, and Boy and Girl Scout meetings at the facility, notes Nancy Aldridge, co-director of the Learning Day Camp. Such events, together with the day camp, she says, have given the center “a respectable place” in the community. Irwin’s children also attended the center’s residential camp and are among the many people whom the center has benefitted.

For more information about the Appalachian South Folklife Center, visit folklifecenter.org

Related Articles

Latest News

More Stories

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

2 responses to “Service, Music and Community at Appalachian South Folklife Center”

-

We’re glad you enjoyed the story! Thank you for your assistance with the process. We mailed 25 copies last week, which should be arriving soon. If you would like more, we would be glad to send them — just email me at Molly [at] appvoices.org and let me know how many. Best, Molly

-

Thanks so much to you and Peter Slavin for the wonderful article about ASFC. Can you send us bulk copies of the newspaper to distribute. We are starting our service work session and will be hosting folks from across the country you would love to learn more about Appalachian as presented in your paper! Our mailing address is P.O, Box 10 Pipestem, WV 25979

Leave a Comment