The 3,000-acre Looney Ridge mine site in Wise County, Va., photographed here in 2015, is owned by Justice family company A&G Coal Corp. Photo by Erin Savage

Examples of this concern can be found by monitoring several A&G Coal Corporation mines in Virginia, which are owned by the family of West Virginia Gov. Jim Justice. These mines have huge reclamation costs associated with them, and it is possible that the state could be left with the bill. These large reclamation costs highlight a potential failure of Virginia’s reclamation bonding program.

Federal mining regulations require all permits to be covered by a reclamation bond. Typically, states administer a bonding program through the state mining agency. In Virginia, the state utilizes both a full-cost bonding system and a pool bond system. When participating in the pool bond, a group of companies put a fraction of their estimated reclamation costs into a shared pool of funds. If one of these companies goes bankrupt, funds from the pool are put forth to cover reclamation costs — but if several companies go under at once, the pool could quickly dry up.

About 50 percent of Virginia’s mine permits participate in the pool bond program. To participate in the pool, an eligible company must provide a permit-specific bond, called a performance bond, which is calculated on a per-acre basis, but is typically lower than a full-cost bond would be. In addition, companies pay into the pool through participation fees and taxes on coal production. If a permit is forfeited, the pool is available to cover additional reclamation costs that the performance bond doesn’t cover.

Many of the Justice family permits participate in Virginia’s pool bond. Further complicating matters, the performance bond for these permits are still self-bonded, a process by which the coal company essentially states they are good for the money, despite the practice being discontinued in 2014 via a general assembly law.

According to documents from the Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy (DMME), there are three Justice family-owned mines of particular concern. Each of these permits are bonded for only a fraction of the estimated cost of reclamation, mostly because they have such a large disturbed area that has not been backfilled or regraded.

Not only are the permits only bonded up to about a tenth of the total estimated reclamation cost, but the vast majority of that money is available through self-bonds. So it’s possible it won’t be available at all. This means that almost the entire $95 million in reclamation costs could fall back on the pool bond. As of Jan. 31, Virginia’s pool bond fund had approximately $9.97 million in it — which is not nearly enough to cover the Justice family’s reclamation liabilities.

Virginia Takes Action Against Justice Family Coal Companies

Coal companies owned by West Virginia Gov. Jim Justice and his family have a history of violating environmental standards and not paying fines and fees. In January, Virginia took action against two Justice companies by revoking two permits and ordering one company to hand over the bond for one of their mines. Read more about this on the Front Porch Blog.

The aforementioned permits are exemplary of a larger problem with Justice family-owned mines that Appalachian Voices has written about before. Since 2012, the Justice family has racked up hundreds of notices of violation and cessation orders. In order to avoid several mines going into bond forfeiture, the DMME entered into a compliance agreement with the Justice family’s companies to clean up the mess. In the intervening years, the companies have continued to rack up violations, and the compliance agreement has been modified several times to account for new violations and missing deadlines. Currently, Justice family companies have three pending bond forfeiture proceedings with the DMME.

Of the three permits in the table above, two were listed in the original compliance agreement and still have not been reclaimed. The Looney Ridge Surface Mine #1 (Permit 1101905) is of particular interest. It can be easily viewed from the top of Black Mountain on Virginia State Route 160 and has often been photographed for news coverage on mountaintop removal. Looney Ridge’s reclamation process was expected to be finished by July 2014, according to the terms of the first compliance agreement. Six revisions of the agreement have happened since then, and the most recent deadline of Feb. 28 has just passed with the site still sitting unreclaimed.

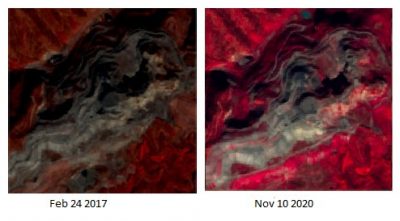

Looney Ridge Surface Mine, permit 1101905. Red in this imagery represents vegetation, gray represents disturbed earth. To see updated imagery please click the photo above or this link.

To track reclamation progress, we have been monitoring satellite imagery acquired from the Sentinel mission with Copernicus satellite via the Google Earth Engine database. The following images are shown in color infrared to better purvey the vegetation differences between bare disturbed land and vegetation This false color scheme replaces near-infrared light which is normally not able to be seen by the human eye in the red color spectrum. It also shifts red light into green spectrum , and green light into blue. This is a standard remote sensing technique for monitoring vegetation.

The continued delays have resulted in several modifications to the compliance agreement schedule and have resulted in little to no revegetation in the past five years. This can be easily seen by a comparison of the two satellite images above. The lack of reclamation on this permit is particularly problematic because of the high reclamation liability, which is roughly $15.8 million.

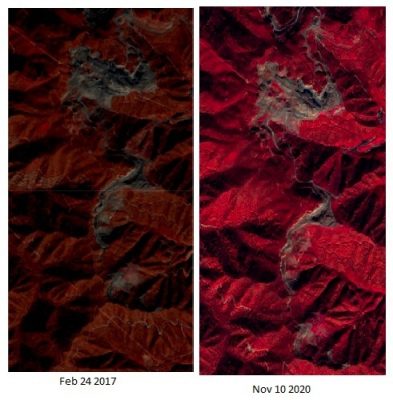

Sawmill Hollow #3 Mine, permit number 1101914. To view imagery that updates with time, please click the photo or this link.

Similar to Looney Ridge, mine permit 1101914 was originally supposed to be reclaimed by June 2015 in the original compliance agreement. Reclamation is now scheduled to begin in March and completed this August, according to the most recent compliance agreement. The satellite imagery to the right shows the mine from February 2017 and from November 2020. The most recent inspection report lists 2,031 disturbed acres on this permit, though that number is only updated annually and might not completely reflect current conditions. This mine has the highest stated reclamation costs of the Justice mines at $54.5 million.

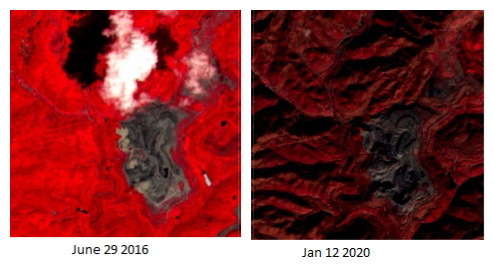

Permit 1101918 has an almost identical story with even greater reclamation costs than Looney Ridge at nearly $25 million. It only has $2 million in self bonds to cover the cost of reclamation, and it could potentially pull in pool bond money to cover some of the reclamation. The bulk of these costs comes from the necessary backfilling and regrading.

This satellite imagery below shows very little revegetation on this permit over the past five years. This permit’s reclamation is not scheduled to be complete till October 2021, as stated in the most recent compliance agreement. We will update the satellite imagery in this blog to reflect current reclamation progress. Still, it has a relatively large disturbed area leading to its high cost of cleanup.

It should be noted that the reclamation cost estimates listed in this blog are about four years old as of March 2020, as there have not been any recent surveys of the permits’ reclamation liabilities. While it is certainly possible that there has been some reclamation work on these permits that would lower the documented cost estimate, the satellite imagery still shows significant disturbance on these three sites without much in the way of improvement. If the permits significant revegetation, the satellite imagery would show up as much more pink and red in the picture.

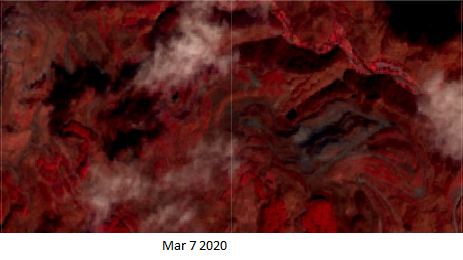

As an example of reclamation we want to see, permit 1101954, also owned by the Justice family, appears to be revegetated except for a portion on the eastern side that has been backfilled and regraded. Vegetation may be starting to establish itself there.

To be clear, reclamation has been happening since these compliance agreements began, but at an incredibly slow pace. New violations have prompted additional modifications to the compliance agreements, and it is difficult to trust the current reclamation deadlines when the compliance agreements have been modified so many times. We will continue to monitor all of these sites through the use of tools like Google Earth Engine, Sentinel Hub playground, and Skytruth Alerts to track the progress of these permits over time. The imagery in this blog will be updated over the course of this year to keep track of the current conditions on these three mines

Author’s Note: This blog was updated on November 12, 2020 to add photos and links to updated imagery for permits 1101905 and 1101914.

Leave a Reply