FIRE Summit Embraces Hands-On Learning in Kentucky

Four Belfry High School students stand with their water-testing equipment in Eastern Kentucky. The students sampled water quality at 10 drinking wells, some near coal mines, and found unhealthy levels of certain elements. Photo courtesy of Dr. Haridas Chandran.

When Belfry High School students in Eastern Kentucky tested groundwater in Pike County for a science project, they never expected to discover contaminants in the area’s drinking water.

“We didn’t go into this saying there was something wrong with the drinking water,” says Hannah McCoy, 18. “We found that this drinking water is not really safe.”

The students found high levels of barium, sulfate and sodium in some of wells they tested. McCoy and classmate Aryn Adkins, 18, say the contamination could be alleviated if there were federal regulations regarding acceptable contaminant levels in groundwater.

In June, the group traveled to Kolkata, India, to exchange ideas and research with peers working on a similar project there.

The project began after Belfry High School was chosen by the University of Kentucky to receive water testing equipment as part of a project sponsored by the U.S. Department of State’s Mission to India that links schools in Kentucky and India to do community-based water quality research and create cultural exchange. Dr. Haridas Chandran, a science teacher at Belfry, wrote in an email that “the successful completion of the project is due to the experiences that we have gained through the projects that we have received from the Appalachian Renaissance Initiative grants.”

The Appalachian Renaissance Initiative, which is funded in part through a U.S. Department of Education Race to the Top Grant, includes the twice-yearly Forging Innovation in Rural Education (FIRE) Summits sponsored by Kentucky Valley Educational Cooperative.

KVEC’s goal is to shift the focus of the classroom away from activities that simply comply with education standards and toward driving innovation in the classroom. The cooperative distributes between 120 and 150 Appalachian Renaissance Initiative grants each year.

KVEC Executive Director Jeff Hawkins says the FIRE Summits offer students, educators and communities tangible reasons to have hope for the future.

“It’s really a celebration of what’s right about education,” Hawkins says. “It’s about kids as makers. It’s about teachers as inspirers. It’s about connecting the passion that a student has innately with a purpose so that they can then advance themselves, but also help others through their own personal advancement.”

During the fall FIRE Summit, educators present proposals for grants that provide up to $1,000 for classroom projects. These micro-investments focus on getting students more engaged and connecting their passion to a purpose.

In the spring, the students and educators meet again for a show-and-tell to share their projects during the spring FIRE Summit. Other projects funded by the grants during the 2017-2018 school year included powering a blender with a bicycle, detecting cancer using plants and gold nanoparticles, hatching trout to release in streams, monitoring water quality in streams, testing air quality for pollution levels, collaborating with NASA scientists to plan an experiment on a satellite, and designing and building drones, as well as student publishing projects.

Through a U.S. Department of State program, the students then traveled to India to present their work at the U.S. Consulate General in Kolkata, India. They also met with Indian students, right, who tested the pH and residual chlorine levels of area river water. Photo courtesy of Dr. Haridas Chandran.

A “health hackathon” held during the summit focused on the opioid crisis. Students created an app that connects residents to local law enforcement to report finding drug paraphernalia. The app pings the location and police respond to collect it. The students also designed a 3D-printed sleeve to drop over a used needle that can be placed in an evidence bag.

Another hackathon project invited high school students to submit anonymously written stories about how opioids and drug use have affected them personally. Sixty of those were compiled into a book that will be published this fall.

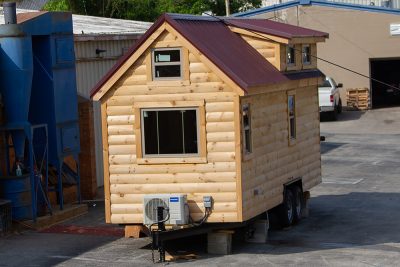

This year’s event also included “Building It Forward,” an ongoing tiny house project. Eight houses were designed and built by students using $15,000 in grants from the Appalachian Renaissance Initiative. They were auctioned on theholler.org in May and June Proceeds go back to the school to fund the next year’s tiny houses.

“In school systems, there are a lot of things that will come and go with funding,” says KVEC Associate Director Dessie Bowling, who founded the Building It Forward project. “That’s why we designed this program to be sustainable, because the school gets the money and it goes right back into their budget to build tiny houses year after year.”

Building it Forward exemplifies what Hawkins says is KVEC’s emphasis on reaching every student to optimize learning.

Each year, teams of Eastern Kentucky students build tiny houses as part of the Building It Forward Project. Students collaborate and learn hands-on skills, and the homes are auctioned to fund the following year’s project. Photo courtesy of The Holler.

“It’s more hands on,” Lee County Area Technology Center sophomore Brandon McIntosh told Kentucky Living magazine. “Over at the high school, it’s a lot of paperwork. Over here it’s take a couple of tests and then you’re out here learning hands on, which is how a lot of kids learn better. I’m not a paper and pencil kind of person.”

Hawkins says small, sustainable programs, such as Building It Forward, are at the heart of KVEC’s goal to help solve the region’s big problems by developing many small solutions through long-term educational strategies.

“If we only picked one thing that we would do to improve our communities, that would have to be an awfully big lever and we would have to have an awfully big fulcrum” Hawkins says. “By having a thousand levers and a thousand fulcrums, we can incrementally advance our communities and lift them up.”

He adds, “Our data tell us that many of our kids who graduate will not come back here to live because the degree that they are in search of or the pathway that they have charted for themselves and the passion that they have, there is not enough diversity of jobs here to satisfy that. Especially in the last five years, with the downturn of the coal industry it has become increasingly important for us to turn our students toward the idea of entrepreneurialism and place-making.”

Related Articles

Latest News

More Stories

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment