Tennessee Crud: Appalachia plays host to yet another environmental disaster

At first, when a 55-foot wall of coal fly ash sludge broke loose from an earthen dam early Dec. 22 near Kingston, TN, the nation barely paid attention.

Initial reports from the Associated Press said there had been an isolated spill of “inert material not harmful to the environment,” according to TVA.

Within two days, as observers with environmental and science organizations began to question reports about the size and toxic nature of the spill, at least five independent toxicological test efforts were launched. These included sampling by the U.S. EPA, Appalachian Voices in partnership with Appalachian State University, and United Mountain Defense working with the

Environmental Integrity Project, Duke University, and others.

The disaster involved 5.4 million cubic yards of material, or an estimated one billion gallons of wet coal fly ash sludge. It was, officially, the largest toxic spill on record, and compares to a 300 million gallon coal slurry sludge spill on Oct. 11, 2000 at Inez, Martin County, Kentucky and to the 11 million gallon oil spill from the Exxon Valdez on March 24, 1989.

The December 22 coal fly ash disaster covered approximately 400 acres with a thick layer of toxic muck. Aerial photo by Dot Griffith Photography

Using descriptions of toxic make-up of the sludge, it was possible to put together estimates of an enormous amount of carcinogens and neurotoxins released into the river. These included a witches’ brew of 2.2 million pounds of arsenic, 5.6 million pounds of chromium VI, five million pounds of lead, nearly a million pounds of thallium and another million of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

Experts expected to find evidence of contamination in the river, and they did.

“Of the 17 compounds we tested, eight of them popped out as significantly higher than they should have been,” said Dr. Shea R. Tuberty of Appalachian State University, who conducted tests along with Dr. Carol Babyak.

“Arsenic was quite hot,” Tuberty said, with levels at 3.06 parts per million, or 300 times higher than EPA’s drinking water standard.

Testing by EPA, Duke University and other independent groups also showed a very high level of toxins in the river.

In rather sharp contrast, results from TVA itself showed a far different picture, with arsenic 20 to 40 times lower than the drinking water standard or sometimes even below detection. TVA conceded that one sample from the river near the spill “slightly exceeds drinking water standards.”

Senate hearing grills TVA chief Kilgore

A composite map of the region surrounding the TVA coal ash spill, pictured in high resolution before the December 22 disaster. Marks indicate direction of river water flow

As TVA’s public relations efforts collapsed, the U.S. Senate Environment committee called a hearing with TVA head Tom Kilgore as its star witness. Kilgore emphasized that TVA would “do cleanup right,” but did not explain how.

Senators repeatedly asked Kilgore for a sign that he took TVA’s leadership role in regards to environmental stewardship seriously.

With cleanup costs so high, one senator asked whether there aren’t cheaper and safer ways to generate electricity. No, Kilgore said: “Solar we don’t have a lot of,” and wind energy would cost “70 cents per kilowatt hour.” In fact, TVA itself charges green power consumers only 2.6 cents more for wind power than for coal power.

Asked about conservation, Kilgore could only point to a feeble program that TVA started within the last few years.

Repeated questions about TVA’s honesty met with stony resistance. New Jersey senator Frank Lautenberg asked why TVA told people that coal ash is not toxic, and not something to be alarmed about. Kilgore had no response.

By acknowledging TVA’s ash disaster problems with an evasive phrase — “this is not a proud moment” — Kilgore could not have given the senators less. In frustration, Senator Barbara Boxer flatly commented on one Kilgore response: “That’s not an answer.”

A week later, two more TVA coal sludge dams failed, a train full of TVA coal fell into a river, and a federal court ordered it to quit stalling on air pollution control equipment in a lawsuit brought by the state of North Carolina.

“Critics would say it looks like the wheels are starting to fall off at TVA,” observed the Chattanooga Times Free Press in an editorial describing the agency’s leaderless drift.

Fly ash had already been controversial

On December 27, Watauga Riverkeeper Donna Lisenby paddled up the Emory River to the site of the spill to obtain water and soil samples, the results of which contradicted TVA’s test results. Photo by Hurricane Creekkeeper John Wathen

Every year, 120 million tons of fly ash make up the residue of 1.1 billion tons of coal burned for electricity. Coal waste is the second largest waste stream in America after municipal solid waste. A train with cars full of a year’s fly ash production would stretch 9,600 miles.

Fly ash has often been used to make grout, asphalt, Portland cement, roofing tiles and filler for other products, but only about 43 percent is stabilized that way, according to the American Coal Ash Association.

Fly ash disposal has become increasingly controversial in recent years. Studies from the 1980s said that fly ash was harmless, but more recent scientific and EPA assessments have sounded alarms.

Environmental groups have been alarmed at the groundwater contamination by heavy metals from coal fly ash. Incidents have taken place all over the country where old fly ash deposits have broken loose, contaminating neighborhoods, threatening health and reducing property values. Fish and other species die quickly when directly exposed to fly ash, and those exposed indirectly accumulate heavy metals in their bodies, harming the ecosystem and posing a serious health risk to anglers.

Undeterred, the coal and utility industries kept insisting that fly ash was harmless. Yet in 2003, EPA identified over 70 sites nationwide where fly ash and similar coal power plant waste has contaminated surface and groundwater. The next year, 130 environmental groups petitioned the federal government to stop allowing fly ash to be dumped where it could come into contact with drinking water supplies.

At the time, EPA put off a decision on new regulations for 18 months. Five years later, regulations have yet to be written, although two years ago, a National Science Foundation report urged EPA to begin regulation.

In the summer of 2007, the EPA released a national risk assessment on coal fly ash disposal. One of the most important factors involved in risk was whether runoff could carry contaminants away from the site and into groundwater.

Cancer risk from arsenic is one of the biggest issues with fly ash. People drinking groundwater contaminated by a coal waste landfill that did not use a plastic liner had a 10,000 times greater than allowable risk of cancer, the EPA said. Other risks include high levels of mercury, lead and other heavy metal contaminants.

Communities in Indiana, Pennsylvania and Maryland have already experienced severe fly ash problems. Water supplies had to be shut down in 2004 in the town of Pines, Indiana, and families were provided with bottled water after molybdenum showed up the town’s drinking water.

In September of 2007, the Boston-based Clean Air Task Force and EarthJustice released a report on the use of coal fly ash to fill in Pennsylvania mines. In 10 of 15 mines examined across the state, groundwater and streams near areas where coal ash (or coal combustion waste) had been used as fill material contained high levels of arsenic, lead, cadmium, selenium and other pollutants above safe standards.

Also in 2007, residents of Giles County, VA filed a lawsuit over coal fly ash landfills being placed by American Electric Power adjacent to the New River. They said that landfills posed a danger to people and to the recreational uses of the river.

In November 2008, residents of Gambrills, Maryland, settled a class action lawsuit against a power company for $45 million after water supplies were contaminated by a fly ash landfill.

Though a National Academy of Sciences report in 2007 said it would be safe to fill abandoned mines with coal fly ash, the Clean Air Task Force and EarthJustice, which have been pushing for more regulations, disagreed: “The public has been told for decades that these coal wastes are not hazardous—it’s time to end that fraud.”

Water sampling shows variety of results

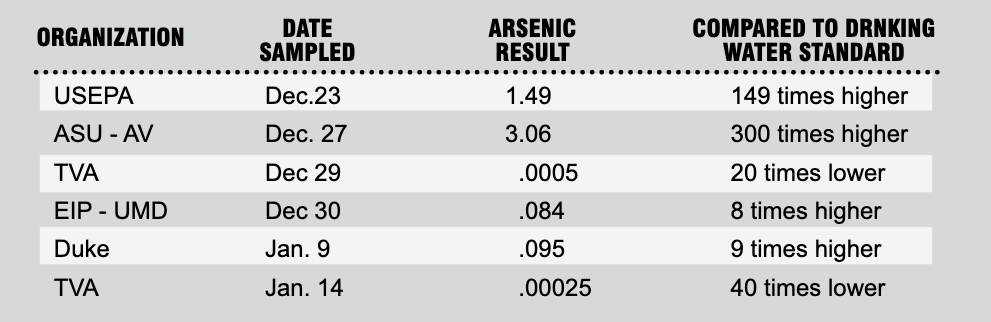

Wildly differing results from heavy metals sampling downstream from the ash spill have led to questions about the methods used by the TVA.

University and environmental groups, such as Appalachian State University – Appalachian Voices (ASU-AV), the Environmental Integrity Project/United Mountain Defense (EIP-UMD), and Duke University, all had significantly higher results for arsenic. The Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) also had a higher result for arsenic than TVA. Here are the sample results for arsenic (total metals) in river water near the spill. Note: Results are given in parts per million (ppm), which is equivalent to milligrams per liter (mg/L). The EPA drinking water standard is no more than 0.010 ppm (mg/L).**

** Sometimes the results are reported as parts per billion (ug/L or micrograms per liter), in which case 3.06 ppm would be 3,060 ppb. For more information on drinking water standards for toxic chemicals, see http://www.epa.gov/safewater/contaminants/index.html

A Month in the Life of TVA

- Dec. 22, 1 a.m.: A 55 foot wall of coal fly ash collapses into Emory River near Harriman, TN, knocking one house off its foundation and damaging 11 others. No serious injuries are

reported. - Dec. 23: First reports indicate that a 1.7 million cubic yard spill 15 homes and covered 300 acres.

- Dec. 24: New York Times describes the spill as a “vast amount of toxic coal sludge.” TVA says it has not encountered any dead fish, contrary to eyewitness reports.

- Dec. 25: TVA says fly ash “consists of inert material not harmful to the environment.” Appalachian Voices flyover provides photos of the size of the disaster.

- Dec. 26: TVA revises spill size to 5.4 million cubic yards, or about one billion gallons. This makes the spill the largest toxic waste event in US history.

- Dec. 27: Southern Alliance for Clean Energy, said officials should more strongly encourage residents to avoid the sludge that surrounds their homes. Greenpeace asks for a criminal investigation. Appalachian Voices and Waterkeepers take citizen samples.

- Dec. 29: TVA says their samples “slightly exceed drinking water standards”

- Dec. 30: New York Times reports that in just one year, the coal ash at Kingston included 45,000 pounds of arsenic, 49,000 pounds of lead, 1.4 million pounds of barium, 91,000 pounds of chromium and 140,000 pounds of manganese. A group of landowners sues for $165 million.

- Jan. 1, 2009: Appalachian Voices releases results of Appalachian State University toxicity tests showing arsenic levels at 300 times drinking water standards. Results are reported in the New York Times.

- Jan. 2: At a news conference, Kingston Mayor Troy Beets drinks a cup of water that he said came from his tap at home. EPA water samples from near the spill found arsenic levels in one sample 149 times the maximum allowable. Samples near the Kingston drinking water intake are within the federal limits, except for thallium.

- Jan. 5: TN politicians agree that the spill is a “wake-up call” for greater environmental and regulatory oversight.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment