Molly Moore | December 15, 2016 | No Comments

By Brian Sewell

Author’s Note, December 19:

In the weeks since this piece was published in the Dec./Jan. issue of The Appalachian Voice, President-elect Trump has chosen climate change deniers, coal and oil executives, and close friends of the fossil fuel industry for top positions in his administration.

For the administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Trump selected Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt. A frequent foe of the agency’s rulemakings and federal court’s interpretation of the Clean Air Act, Pruitt describes himself as having “led the charge” against the EPA’s “activist agenda.” Trump’s Secretary of Commerce-Designate, Wilbur Ross, is a billionaire investor with strong ties to the Central Appalachian coal industry and a history of disregard for regulations that protect miners, communities and the environment. The president-elect’s choice for Energy Secretary, former Texas Governor Rick Perry, will be tasked with leading an agency with budget of $30 billion that Perry once advocated for eliminating altogether—despite famously blanking on the department’s name during a presidential primary debate in 2011.

Beyond the president-elect’s appointments, his transitions team’s actions on energy and the environment are causing serious concern among environmentalists and the scientific community. In early December, Trump’s transition team sent a questionnaire to officials at the U.S. Department of Energy requesting, among other things, a list of individuals involved in international climate negotiations and the programs associated with President Obama’s Climate Action Plan. Agency officials refused to respond to the controversial questionnaire and Trump’s team has since said it “was not authorized.”

With a month until the inauguration, Americans concerned about climate change and other environmental threats have little reason to believe that Trump will moderate his anti-scientific positions. He has instead surrounded himself with individuals that share those views. In response, environmental, economic and social justice advocates have amplified their calls to resist and defend against the regulatory rollbacks that Trump and soon-to-be members of his cabinet support.

— Brian Sewell

———-

Aside from his promises to “save the coal industry,” Donald Trump has yet to address the need for investments to stimulate economic activity and job opportunities in Appalachia. Photo by Gage Skidmore, licensed under Creative Commons.

Ten days after winning the White House, Donald Trump called Jim Justice, the billionaire coal company owner and governor-elect of West Virginia, and asked him to pass along a message to residents of the Mountain State: “We are going to get those coal miners back to work.”

As he vetted candidates for cabinet-level positions, the president-elect made clear that the concern he showed for the coal industry during the campaign continues. Less clear is how exactly he will attempt to revive the struggling sector — or how he will confront the collateral damage to human health, the environment and the climate that could result.

Trump made bold promises throughout a campaign that often put feelings before facts. He has since waffled on a variety of stances, clouding expectations and adding to the speculation about his plans for the country.

It’s impossible to fully parse the factors that led to Trump’s win. Having never served in public office or in the military, he was described as less qualified than a “speck of dirt” by Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul, who later supported Trump. Other members of Congress claimed that Trump disqualified himself many times over during the course of the campaign.

Cast in a gold-plated veneer of populism, his speeches dredged up enmity toward Hillary Clinton and immigrants, expressed loudly by crowds chanting “lock her up” and “build the wall.” Among other popular targets were President Obama and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which Trump has called “an absolute disgrace” and accused of killing America’s energy companies.

In Appalachia, the electorate’s anxieties — whether stemming from economic, demographic or social change — were often viewed through the lens of coal and manufacturing job losses and economic stagnation. Clinton, already facing an uphill battle in the region, hurt herself even more when she told a town hall audience, “We’re going to put a lot of coal miners and coal companies out of business,” referring to the transition to cleaner energy sources already underway.

The gaffe became a sound bite used to validate Trump’s foreboding about coal’s future should Clinton become president. Inheriting the Republican Party’s mantle of ending a perceived regulatory “war on coal,” Trump assured mining communities of his allegiance to the industry. When the dust settled on the day after the election, Appalachia’s deep red complexion appeared again.

Kentucky was the first state called on election night, and it was quickly called for Trump. In Perry, Pike and Harlan, the state’s top three coal-producing counties, he won an average of more than 80 percent of the votes. Elliott County saw the largest swing toward Republicans in the country — 23 points more than in 2012 — and for the first time in its history voted against the Democratic presidential candidate. West Virginia, Tennessee and North Carolina also went red.

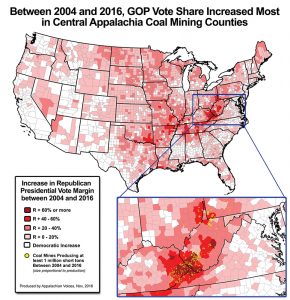

Click to enlarge.

Central Appalachian coal mining counties have shifted more Republican since 2004. Sources: 2016 election data from Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections; 2004-2012 election results from the National Atlas; Mine data from MSHA, Part 50 Address/Employment files, 2004-2016.

Clinton narrowly took Virginia, as Obama did in 2012, but every county in the far southwestern corner of the state voted for Trump by larger margins than they did for Mitt Romney four years ago. Most importantly for the election’s outcome was the fact that Trump’s strident take on energy, manufacturing and international trade resonated beyond the coalfields and throughout the Rust Belt.

After voting for Obama twice, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin all flipped Republican this year. In those four states, Trump won 47 counties that Obama carried in 2012, and he outperformed Mitt Romney in dozens of Appalachian counties by 10 points or greater.

Clinton’s lead in the national popular vote exceeded two million, and the counties she carried represent nearly two-thirds of the country’s economic output — 64 percent compared to Trump’s 36, based on county-level data compiled by the Brookings Institution. But Appalachia’s choice was clear.

Trump has, at various times, vowed to “encourage the use of natural gas” and “save the coal industry,” apparently unaware that competition from cheap gas is the primary driver behind coal’s domestic decline. He claims that rescinding regulations on fossil fuel production and use will allow wealth to “pour into our communities.” But even a casual survey of Appalachia’s history of resource extraction reveals how the region’s wealth has been concentrated by absentee landowners and corporations.

In recent decades, the trend has been toward the industry’s long-term and irreversible decline, and the pain felt in Appalachia has been especially acute. Appalachian states have lost more than 35,000 mining jobs in just five years, a decline of nearly 60 percent since the end of 2011. Over that period, job losses in the region accounted for more than 80 percent of coal job losses nationwide.

But long before the proliferation of fracking and the growing role of natural gas in the nation’s energy mix, the mechanization of underground and surface mining led to lower employment even as coal production climbed.

Underneath all of the rhetoric there is widespread recognition among coal and utility executives, energy analysts and some in mining communities that it is not within Trump’s power to save the industry.

After meeting with Trump in May, Murray Energy CEO Robert Murray described him as “sobered” when told the coal industry cannot bounce back. A vehement critic of the Obama administration’s environmental policies, Murray suggested that Trump moderate his message to avoid creating “expectations that aren’t real.”

Even Kentucky Sen. Mitch McConnell, one of the primary instigators of the “war on coal” narrative during Obama’s presidency, lowered the bar. “We are going to be presenting to the new president a variety of options that could end this assault,” McConnell said at the University of Louisville a few days after the election. “Whether that immediately brings business back is hard to tell because it’s a private sector activity.”

Still, by rolling back environmental regulations and reducing the federal government’s role in their enforcement, Trump may be able to slow the bleeding — but not without potentially opening new wounds.

Environmentalists who have cheered falling carbon emissions and coal consumption worry the Trump administration’s policies could lead to long-term environmental and climate consequences that far outweigh any near-term economic gain. Under his watch, federal agencies are likely to take a more shortsighted approach to evaluating and permitting fossil fuel projects, including mountaintop removal coal mines and interstate oil and gas pipelines.

Trump says his administration will focus on “real environmental challenges, not phony ones.” But in his first 100 days as president he has pledged to lift the moratorium on federal coal leases in western states and rescind regulations including the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Stream Protection Rule and EPA rules limiting methane emissions from oil and gas operations. Trump also promises to kill the EPA’s Clean Power Plan, which instructs states to limit power plant carbon emissions, and withdraw the United States from the 2015 Paris climate agreement, which went into effect in November.

These, and many other of the incoming administration’s priorities, closely align with those of coal’s proponents in Congress. Where congressional action is needed to weaken environmental rules, President Trump will likely have many allies. His administration can take other steps — including walking away from the Paris deal — largely through executive action. Even before taking office, Trump’s anti-scientific stance on climate change has begun alienating key international partners like China and the European Union.

Based on recent statements, Trump’s grasp on the reality of climate change remains tenuous. When asked by The New York Times in a Nov. 22 meeting if he believes human activity contributes to global warming, he said that it “depends on how much it’s going to cost our companies.” America is sure to continue producing examples of climate leadership, whether in the private sector or at the state level, but there is no indication Trump’s administration will do anything but harm.

“The very thought of a Trump administration overseeing national energy policy will inevitably shift more of the action to the states,” David Victor, a professor at the University of California-San Diego’s School of Global Policy and Strategy, wrote in a post-election essay for Yale Environment 360.

On one hand, that could lead to a greater emphasis on efforts to reduce emissions in states like Virginia, where Gov. Terry McAuliffe has established a working group to recommend carbon-cutting strategies. But it could also embolden politically powerful industries in states where regulators lack the resources or willpower to adequately enforce environmental laws.

For all the attention paid to distressed Appalachian communities during the campaign, Trump has yet to address the growing need for targeted federal investments to stimulate economic activity and job opportunities in the region. Yet, when compared to Trump’s promises to save the industry, neither Hillary Clinton’s $30 billion plan for revitalizing coal communities nor existing White House initiatives received much national attention during the campaign. That’s not to say these ideas aren’t catching on in the coalfields.

Last fall, two dozen local governments in Central Appalachia passed unanimous resolutions in support of the Obama administration’s POWER+ Plan, a set of budgetary earmarks and policy proposals to bolster economic diversification in communities that have historically relied on coal. Through the related POWER Initiative, the Appalachian Regional Commission has awarded a total of nearly $47 million to more than 70 economic development projects across nine Appalachian states.

Appalachian lawmakers in the House and Senate have also introduced bipartisan legislation to invest in the region’s economic future. One bill, the RECLAIM Act, would direct $1 billion of existing money from the federal Abandoned Mine Reclamation Fund to clean up polluted post-mine sites and repurpose them for an economically beneficial use.

A September poll conducted by Public Opinion Strategies, a Republican polling firm, found that 89 percent of registered voters in Kentucky, Virginia, West Virginia, Tennessee, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Indiana support the RECLAIM Act. By a two-to-one margin, those polled believe that elected officials should prioritize attracting new employers and transitioning the region’s economy rather than fighting regulations.

If Trump plans to refocus the federal government’s role in response to the frustrations of rural communities that overwhelmingly endorsed him, he will need a clear-eyed approach to the challenges facing the region. “Nobody knows the system better than me,” Trump told the country upon accepting his party’s nomination, “which is why I alone can fix it.” Facing enormous odds, he now has a chance to try.

Like this content? Subscribe to The Voice email digests