The passage of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA) in 1977 set in motion many protections for communities and the environment in coal-bearing regions. Though not perfect, the law improved mining practices and reduced the risk of companies leaving strip-mined lands without taking steps to restore them. To address mines that had already been abandoned prior to passage of the act, it created the Abandoned Mine Land (AML) reclamation program. The program is funded by a fee on coal production, so that the industry as a whole takes responsibility for mining’s legacy.

The AML fee was initially authorized for 15 years and has been periodically reauthorized by Congress over the last four decades. The fee is currently set to expire in 2021 unless Congress acts to extend it again. Reauthorization not only gives Congress a chance to extend the fee, but also to make improvements to the AML program.

Successful reclamation of abandoned mine lands relies on three key elements – identification of AML sites, money to fund reclamation, and a system to distribute funding to where it is most needed. The current AML program needs improvements in each of these elements.

AML Inventory

The federal Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE) maintains an inventory of AML sites around the country, known as the electronic Abandoned Mine Land Inventory System (e-AMLIS).

The initial inventory was created by OSMRE based on aerial imagery obtained in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Since then, the inventory has been updated through a combined effort by states and OSMRE. States that have an abandoned mine land program are responsible for identifying and reporting sites to OSMRE for inclusion in the inventory. OSMRE is responsible for the inventory in 11 states that do not have approved AML programs.

While OSMRE provides support in updating the AML inventory to all coal-bearing states, the task remains expensive and time-consuming. Not all states have the resources to adequately identify and inventory AML sites. Additionally, previously unknown AML sites are discovered on a regular basis, and new AML features like sinkholes can develop over time, so many state inventories continue to grow.

AML sites are ranked by a priority scale from 1 to 3 — priority 1 and 2 sites pose a risk to public health and safety, while priority 3 sites do not. Currently, the law only requires OSMRE to inventory priority 1 and 2 sites. Many priority 3 sites are excluded from the inventory, though they often contribute significantly to environmental degradation, lack of economic productivity or development, and the potential development of human health impacts.

An accurate AML inventory system is imperative for understanding the scope of the problem, where funding needs to be directed, and how much funding is necessary.

OSMRE is required to approve the addition of new AML sites into the AML inventory, but its approval is not guaranteed. In 2017, Robert Rice, Chief of the West Virginia Office of Abandoned Mine Lands and Reclamation, testified before Congress that OSMRE removed many of West Virginia’s AML sites from the inventory. At that time, the inventory included $1.21 billion of AML sites in West Virginia, but the state’s own inventory included $4.5 billion. In addition, cost estimates for specific sites may be decades old and therefore not adequately represent the true cost of reclamation.

An accurate AML inventory system is imperative for understanding the scope of the problem, where funding needs to be directed, and how much funding is necessary.

AML Fee

The AML fee paid by coal companies provides the bulk of the funding for AML reclamation. In 1977, the fee was set at 35 cents for surface-mined coal, 15 cents for underground-mined coal, and 10 cents for lignite coal. Since that time, the fee has steadily declined for several reasons: Congress has decreased the fee several times; a decline in coal production has reduced fee revenues; and the fee has never been corrected for inflation. The current fee structure is about 23% of what the original fee would be if corrected for inflation.

Though the AML program has distributed $5.7 billion to states and Native American tribes for reclamation since its inception, there are $10.6 billion of unfunded remaining AML needs in the inventory. Due to the deficiencies outlined above, this estimate is likely very low. There is currently an unspent balance of about $2.3 billion in the AML fund.

Distribution of AML funds

The current AML fund distribution system is complex. Distribution depends on whether a state is “certified” — meaning that it has reclaimed all priority 1 and 2 sites — or “non-certified.” The funds fall under four categories:

- state and tribal share funds

- historic coal funds

- minimum program make-up funds

- certified in lieu funds

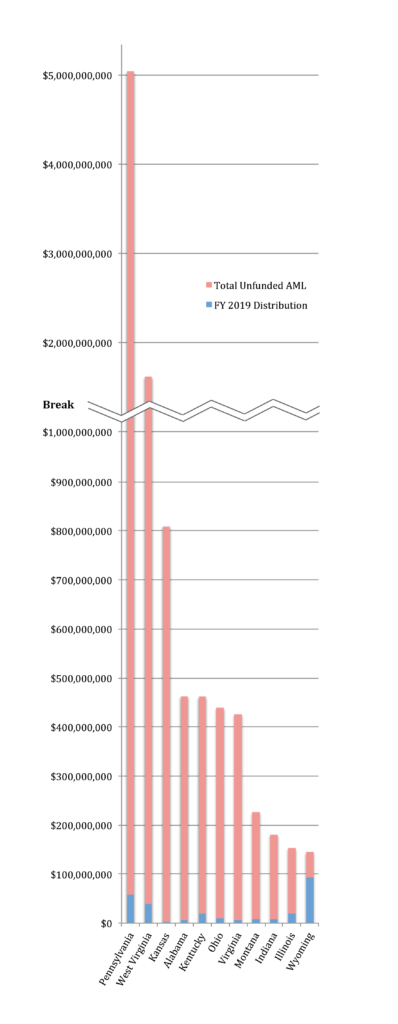

Total outstanding AML costs and fiscal year 2019 AML fund distributions for the 11 states with the highest outstanding AML cost, based on OSMRE e-AMLIS data. Outstanding costs may vary depending on level of accuracy for each state’s inventory and cost estimates.

Initially, the AML program relied on share grants for distribution — coal companies in each coal producing state contributed money based on production, and the states received a portion of that money to use for AML reclamation. Currently, each state receives 50% of the AML fee collected from that state in the previous year, either through the share grants, financed through the AML fund, or through in lieu grants, financed by the general treasury.

In recent decades, as coal production shifted from historic coal states with a lot of abandoned mine lands, to states that did not produce much coal prior to 1977, changes to AML fund distribution have been made to ensure that money continues to be directed to states most in need of AML reclamation.Historic coal grants began in 1996. Through these grants, non-certified states (which still have priority 1 and/or 2 sites to reclaim) receive a portion of AML money based on that state’s total coal production prior to 1977. Non-certified states that receive less than $3 million per year from share grants and historic coal grants receive additional funding from the minimum program make-up grant to bring that state’s distribution up to $3 million.

Current AML fund distribution is based on current coal production (via total AML fees contributed) and historical coal production, not on actual AML reclamation need. The result is that AML fund distribution is not proportional to outstanding AML reclamation costs.

Recommendations

AML Inventory: With the help of state AML programs, OSMRE should undertake a complete update of the AML inventory across the country, and include all priority 1, 2 and 3 sites, as well as updated cost estimates for reclamation. The ability to accurately assess need is wholly dependent on an accurate AML inventory and up-to-date cost estimates.

AML Fee: The AML Fee must be reauthorized by 2021, for at least an additional 15 years. To cover existing known reclamation costs, the fee would need to roughly double at reauthorization, and be sustained until 2050. See our fee structure and justification here.

AML Distribution: The AML distribution structure should be reworked so that it is largely based on need. One change to accomplish this would be to increase the minimum program makeup grant for non-certified states — as coal mining decreases, especially in the East, some historic coal states are even less likely to receive adequate funds from the current AML distribution structure.

I’ve highlighted three main structural issues in the current AML program that, if adjusted, could help to ensure that sufficient money is available to reclaim abandoned mines and that the money is distributed where it is most needed. A more complete analysis of the AML program, along with additional policy recommendations can be found here.

Leave a Reply