AV's Intern Team | February 7, 2014 | 19 Comments

By Kimber Ray

Attempting to trace the origin of the Melungeon people is akin to pursuing the source of the Cumberland River coursing through their historical territory. Like the waters of the Cumberland Gap, where neighboring streams weave through Tennessee, Kentucky and Virginia to meet among the rolling crests of the Appalachian Mountains, the Melungeons — a mixed-race population of Appalachia — are the product of a great fusion. Yet where had these waters passed before they arrived in Appalachia?

With a map of the Cumberland Gap spread on the table, Sylvia Ray, mother of Tammy Stachowicz, researches the residences of her Melungeon ancestors.

If the water had traveled along the same path as the Melungeons, some might speculate that it had pooled into swimming holes for the lost colonists of Roanoke Island, off the coast of North Carolina. Others may suggest these were the same waters that had carried the notorious ships of 17th century Portuguese slave traders across the Atlantic Ocean. While any of these stories may be true, each one blunders over an essential truth: the Melungeons— like the river — are an indisputable presence that is greater than any far-flung origin.

“You can’t pin down a definite definition for Melungeons,” says Tucker Davis, a freelance journalist and self-identified Melungeon from Buchanan County, Va. He recalls a youth spent exploring his rural mountain community of Grundy, where everyone had a different story about what it was to be Melungeon. From neighbors recounting tales of African or Native American lineage, to a Sunday school teacher who said they could be identified by a small knot of bone on the back of their heads, no one could say who the Melungeons were with certainty.

A popular misconception is that Melungeons can be identified by their dark skin and piercing blue or green eyes. This may have been true historically but, by its very nature, a racially mixed group will manifest in countless expressions over time.

The quest to conclusively characterize Melungeons may be spurred by the abiding mystery of whether they were in Appalachia even before the English. William Isom, a coordinator for the grassroots Community Media Organizing Project, explains that his family had long passed down an oral history of their Melungeon heritage; yet he was the first to conduct more extensive academic and genealogical research on his family’s deep-rooted history in the Cumberland Gap region of Tennessee.

“I’ve always been really intrigued with genealogy and keeping records even as a kid,” Isom states. “So I’ve always been interested in copies of the family tree and family photos. It’s a personality thing; I’m that guy who likes to archive things and keep these scraps together.”

From sifting through these pieces of the past, Isom says he’s settled on the idea that Melungeons are ambiguous because the population is historically mixed. In vivid detail, he speaks of how the English first scaled the Appalachian mountains in the 17th century and encountered people of color — neither Native American nor black — who dressed like Europeans, lived in houses, and spoke some kind of English, which they used to announce that they were Portuguese.

But this history still would not provide a decisive answer of origin: the Portuguese were the first slave traders, and their population included Jews, Muslims and North Africans. What is known with more certainty is that the term Melungeon did not appear in print until 1813, where it was used to ascribe mixed-race identity to others.

Tucker Davis has documents from this early time period of his own ancestors appearing in court, fighting the theft of their land after having been labeled Melungeon. According to Isom, discrimination and the resentful sentiment of being labeled a Melungeon can still be very tangible in northeast Tennessee.

Recalling folklore that would brand Melungeons as bogeymen, Isom says that children would be warned, “Don’t go out in the woods at night, the Melungeons will get you.” In his community, it was not uncommon for fights to ensue if the word was thrown around.

“If you called someone Melungeon, it meant you hated that person to the core of their being,” Isom says. “But now it’s fine,” he adds, because “most of the Melungeon population has assimilated into broader society, so the threat — the dread — of getting your property taken, or being murdered is no longer a reality.”

Growing acceptance of Melungeon identity is the most recent emergence in this complex narrative. “I knew no one that referred to themselves as Melungeon prior to 1990 because until recently in some areas it’s still a term you don’t say out loud — it’s a racial epithet,” states Isom, who himself became engaged with the grassroots Melungeon movement in the mid-’90s.

Ray is preparing a meal in this 1968 photograph. Many recipes were passed down by her Cherokee grandmother in southeastern Kentucky. Photos courtesy of Tammy Stachowicz

Isom asserts that there are actually two kinds of Melungeons: racial Melungeons and cultural Melungeons. While a racial Melungeon is someone from a historically mixed community, Isom explains, a cultural Melungeon is “poor folks — who make up the bulk of people in Appalachia — who might not have racial disparities to deal with, but share a cultural and economic identity. They understand that even though they might be white and from the mountains, they’re still not quite white enough, they’re not quite assimilated into the mainstream, they’re not marketable.”

The idea of racial status forming the basis of identity is a persistent — and harmful — belief. “Race itself is so socially constructed,” remarks Tammy Stachowicz, a diversity instructor at Davenport University in Michigan. For Stachowicz, her experience as a Melungeon had nothing to do with her skin tone.

Stachowicz discovered her Melungeon origins while searching for the source of her family’s puzzling heritage. She grew up on a farm in Michigan, where her family carefully tended their garden and orchard and raised animals including horses, goats, pigs and chickens. Although she recalls these memories fondly, Stachowicz felt throughout her childhood that there was something about her family that was different.

“Nobody else was so self-reliant — canning, freezing and growing their own food,” she says. Other children in the neighborhood made sure that she knew just how unusual this seemed. “We got teased mercilessly. Kids behind us on the school bus would throw spit wads and make animal noises,” Stachowicz adds. In her journey to understand her identity, she conducted her thesis work on Melungeons and came to a versatile conclusion: “Nature doesn’t make you Melungeon. Nurture does.”

Yet despite this conviction — one which she found validated by various Melungeons she spoke with — many people have never stopped trying to pinpoint a firmer genetic source of Melungeons. With the advances of modern technology, this fascination has taken on a new form.

Most recently, researchers published a Melungeon DNA study in the Journal of Genetic Genealogy. The final results examined only a “core group” of Melungeons — one that excluded many self-identified families — and concluded that Melungeons are primarily sub-Saharan African and European. Tucker Davis is unconvinced. “Even if a group of researchers vote on some technical definition of Melungeons, it won’t matter,” he says. “It won’t change what it means to be Melungeon.”

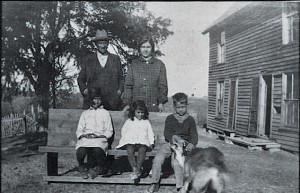

William Isom found this undated photograph of his great-great-aunt and uncle, Lillian Isom and Henry Cloud, while searching for information about his family’s heritage in northeastern Tennessee. Photo courtesy of William Isom

In a nod to the damaging effects of assigning an identity to others based on race, the American Anthropological Association wrote in 1999 that “humans are not unambiguous or clearly demarcated … race is an arbitrary and subjective means of classifying groups of people, used to justify inequalities … and the myths impede understanding of cultural behavior.”

This plight is poignantly revealed in Appalachia, which has long struggled to shed stereotypes imposed by others. For Melungeons, this struggle is magnified. Despite sharing the Appalachian cultural heritage — a story of independence and a fighting spirit shadowed by mistrust from generations of exploitation — Melungeons have suffered harsh discrimination from their “whiter” neighbors.

Prejudice against Melungeons has waxed and waned over time, in step with shifting racial perceptions in the United States. Through the emergence of racial slavery in the late 17th century, wealthy landowners sought to keep the poor under control by pitting racial groups against one another. Despite the shared heritage of many Appalachians, the stigma that came to be associated with race led much of the public to speak of “purity.” Those who could not conceal a multi-racial background encountered countless civil, educational and economic limitations.

Yet prior to — and even following — the rise of racial slavery and legal segregation, people of all different backgrounds were sharing cultures and marriages, adding to the identity of Melungeons today. As Davis explains, the story of Melungeons is not just one of discrimination, but also of diversity and community. “When I think of Melungeons, I think of unity,” he states.

In revealing the legacy of Melungeons, Isom says that he wants to “dispel the myth of Appalachian whiteness and dispel the cut-and-dry story of American settlement in Appalachia: that there was Cherokee, then the Scotch-Irish came, then the TVA, and mountaintop removal — that’s Appalachia.” He adds, “I want to mess that up as much as I can.”

Exactly where Melungeon identity ends and Appalachian identity begins is uncertain. Davis suggests that maybe being Melungeon is just a state of mind. Stachowicz likens it to a venn diagram, pointing out that with generations of Appalachians and Melungeons all living together, “you can’t know one without the other.” Then again, maybe it’s not so surprising that there is no single element that can define the shared experience of identity.

Like this content? Subscribe to The Voice email digests

A lot of the folks identified as Melungeon were/are my people. Hancock Co. Tn is identified as a Community or Village of these people. Mainly, the Collins, Gbsons, Mullins, Roberts, Williams, Sextons and Goins made up this group of people. Recently research has established the folks to be primarily Indian. (Cherokee) Robert K Thomas, Dr Thomas Walker’s journal, the Sycamore shoulds treaty, the path deed as well as other documented facts (records) verified who most of these folks, my ancestors and ki n folks were or are.

This is so interesting. My husband’s family is from Mingo County, W.Va. and he is related to both the Hatfields and McCoys. I’ve always been intrigued by these ‘people’…. keep this up! and thanks

One of he most interesting things I’ve read in a long time. I had no idea….

I have found through the Helton/Owl family (Cherokee) to be related to the Goins (mulatto). I am still looking for another Indian family of Madox/Maddox that appear to be related to the Matoy/McGray family (Cherokee). From the depositions of people who appear to be non-Anglo, under different circumstances – Rev War Aps, litigation and the like – they shared the unrelentless denial of land ownership, denial to testify in an Anglo question (trial, litigation, etc.), and the right to exist (kill on sight).

I have found two different people in the exact same records with the exact same name. I suspect it was a way of hiding in plain sight. This research is maddening and fascinating at the same time.

We need to have more of the true history of this area see the light of day. The story is begging to be told.

My female Madox mtdna is from East India.

“Exactly where Melungeon identity ends and Appalachian identity begins is uncertain.” This is a brilliant statement, which I endorse from the perspective of a lifetime of moving westward across the southern border of Virginia. In Hampton Roads, where I’m from, I never ran into anyone who had ever heard of Melungeons, not once. In Halifax County where I worked for many years, I rarely met anyone who was not familiar with the word. In far Southwest Virginia, everyone has known Melungeons and many acknowledge kinship connections. Appalachia has the reputation of “all white” but people do not realize the implication– anyone who was “mulatto” or “Indian” in Virginia or the Carolinas could migrate to Kentucky or Tennessee and become “dark skinned white” called behind his back “Melungeon.” Triracial heritage is very real in places considered “all white.” With the Indian, African, Iberian, South Asian, etc. elements now so diluted to 1% or 2% of the DNA, it’s invisible to outsiders who see Appalachia as “all white.” But in certain parts of Appalachia Melungeon heritage is in many local families’ background.

Would like to contact Cleland Thorpe in regard to where I might be able to find and read the source of research regarding the names Sexton and Goins (both names of my ancestors (Grandmother and Great Great Grandmother’s maiden names)). Have been seriously researching for several years, and having some difficulty establishing the Cherokee connection. I have genetic testing results through 23 and Me, under the name Judy DeArmond, or can reach me on facebook page Judy Cunigan DeArmond. Thanks for any help.

I appreciate the suggestion that people can be non-genetic Melungeon. I had never heard the term Melungeon until a few months ago when I ran across the word in my genealogy studies. This group I am working on lived in the area, had friends and in-laws with the names that appear in the Melungeon surnames list. Learning about this culture has been helpful and I am still looking. Now I guess I can identify that my family was at least culturally Melungeon.

I just found out that our family is Melungeon a year ago- mom’s family line was born and raised in the Cumberland Gap- TN. And it explains why my DNA is so diverse- with dark kinky curly hair and green eyes with fair skin- DNA shows NA, African Pygmy, Portugeuse, Spanish, Jewish, European, French and more. My dad is from Jamestown VA- Harris/Overton line and mom is Buchanan, Curtis etc line. I am still looking at Davis and Bryant lines- very line. But researching Melungeon has helped me to understand why the DNA is different- Thank You for article.

I am a Collins for years there has been a story that the woods were ran by red and black Collins. We lived on the Tar Tar River in North Carolina. We never knew until this. I have my DNA English African Caucasus Jewish Italy Andy Greece

I am a Collins for years there has been a story that the woods were ran by red and black Collins. We lived on the Tar Tar River in North Carolina. We never knew until this. I have my DNA English African Caucasus Jewish Italy & Greece

My father-in-law told my husband , his son, that his family Davis , was ran into the mountains because “there were people that did not like them . this sounds to me his family were from Melungeon heritage, this Davis family , as I hear it, were Cherokee , My husband lower teeth are shaped like a shovel description I had read about .

My family was from Virginia as far back as 1800, the surname was Saunders. I’m very intrigued about them, because the race of one person was, mulatto in 1870, white in 1880, and black in 1900 for the same person. I also noted several of them men married women within their own family. Some women’s maiden name and married surname was exactly the same.

Dwite this person was most likely NA, read about Walter Plecker and how VA changed peoples racial designations and his hit list families, most have mixed Native blood that was hidden.

My daughter is a Fint, her grandfather was a Lindsay from eastern TN, my daughter is the picture definition of melungeon. Her skin is so dark every one ask is she mixed and her eyes are brilliant green. Her hair is one of a kind color deep golden brown.

Her Grandmother who was married to the lindsay was definetly part Cherokee but her grandfather and father look like her. Her brother has the same very dark brown skin but he has brown eyes and then their youngest sibling was born with normal white skin and blonde hair and brown eyes all of them are biological siblings.

I descend from the colonial families Collins, Sargeant, Goodwin, Nichols, Taylor, Nelson, Thayer, Martin and Davison. Of New Hampshire, Virginia, Connecticut, Masschusettes and New York. My DNA has half Irish and Welsh (dads side) but my mom and have Very different estimates!

Me: Iberian, N W & S Eur, Italian and Greek, N African, Ashkenazi and Indigenous Amazonian.

MOM: Irish, British, East European, Broadly Eur, Ukranian, Ashkenazi and Neanderthal!

Would being multi-ethnic, possibly Melungeon explain all that?

This is a very interesting article. I have been helping my father-in-law find his family history now that I have had the only male that will carry on his family name. We have visited Appalachian towns to check the actual documents, as online ancestry sites listed them as colored or black. Piecing together family legends, historical, modern records and interviews in the local communities has been revealing.

The Appalachian family married into WV miner families that self-identified as gypsies. Oddly the recent gypsy immigrants look like the melungeoun family.

Here is an excerpt from a history of gypsy people that surely matches the story behind the melungeon origins:

[Portugal banned Gypsies in 1526, and any of them born there were deported to the Portuguese African colonies. The first record of Gypsy people being deported to Brazil appears in 1574. Whole groups of them were sent to Brazil in 1686. There were also times in the seventeenth century when the policy was only to send Gypsy women to the colonies, while the men were enslaved on galleys.]

From: https://owlcation.com/humanities/The-Gypsies

So there you have the Portuguese, African, Early Americans (and also covered in the article is the Jewish community being associated or by decree being lumped in with the gypsies.)

Another fact and history I have come across is the story of the Appalacian family being horse theives. The article link above repeatedly sites gypsies in Europe being horse thieves.

A lot of the folks identified as Melungeon were/are my people. Hancock Co. Tn is identified as a Community or Village of these people. Mainly, the Collins, Gbsons, Mullins, Roberts, Williams, Sextons and Goins made up this group of people. Recently research has established the folks to be primarily Indian. (Cherokee) Robert K Thomas, Dr Thomas Walker’s journal, the Sycamore shoulds treaty, the path deed as well as other documented facts (records) verified who most of these folks, my ancestors and ki n folks were or are.

hi. My name is carol smith. i am just today searching the possibility of having melungeon heritage. i saw three names ,nelson,dennis and luce. more since i got back my family tree dna.